A Change of HeArt

By Theri Anderson

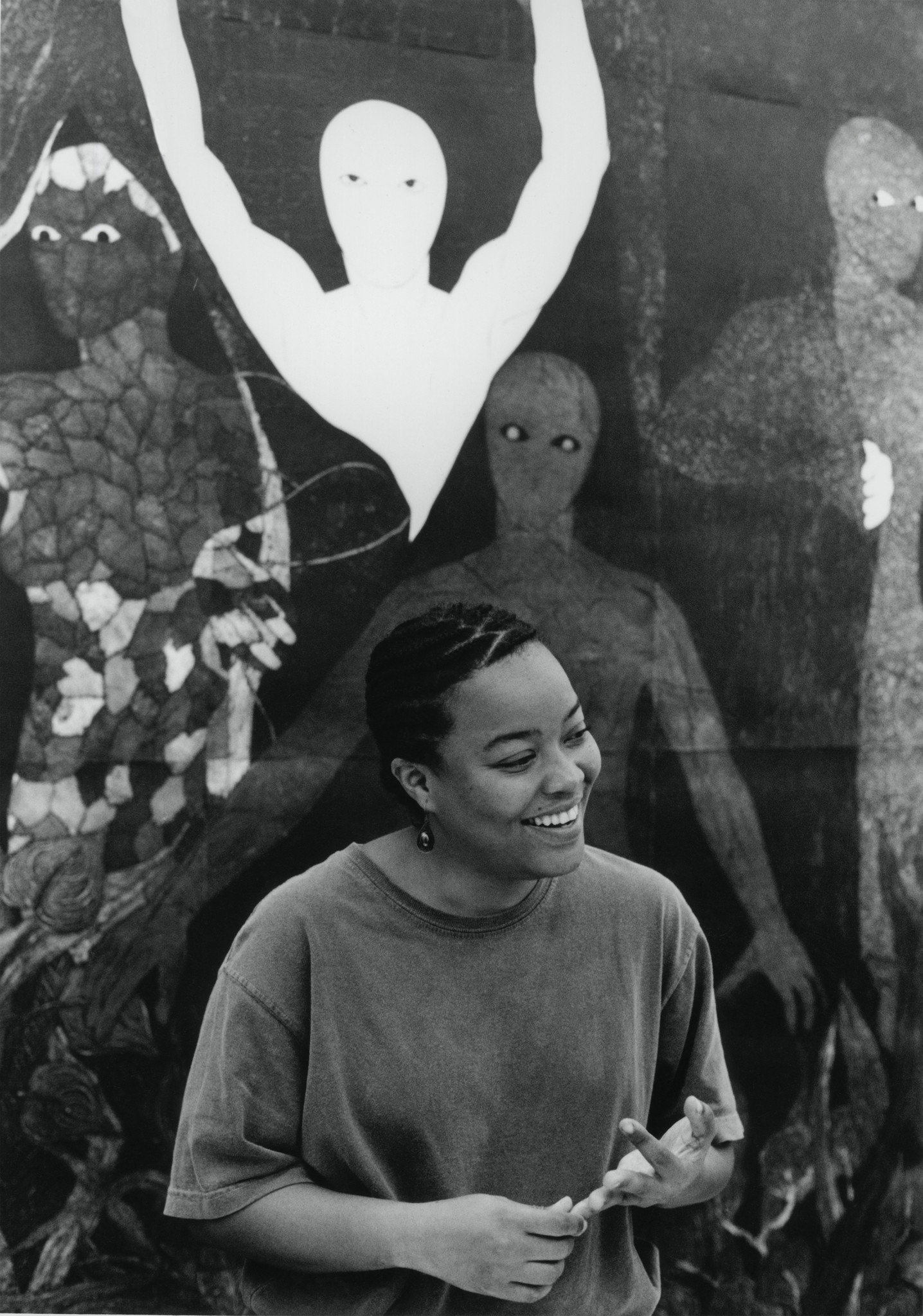

Photo via The Whintey Museum of American Art

Artists make art when tensions arise in society. Art has the uncanny ability to foster democracy when we let it. In the 1980s, during the Reagan era, there was a united politicized culture just beginning to emerge. The political art of the 80s united an entire generation of artists, also known as the “baby boomers.” People looked to artists to help them conceptualize the War on Drugs, the U.S in Vietnam, Nixon, Watergate, and other policy changes. Artists banded together politically as a reaction against the predominant conservative mindset. Today, we see a similar resurgence of politically driven artistry. Similar to artists of the 80s, artists today are presented with the same arduous task to come up with original art that can help us better understand the times in which we are living.

Remnants of the current political atmosphere are seeping through the perspectives of various art institutions around NYC. El Museo del Barrio is exhibiting a collection of works under the title uptown: nasty women/bad hombres in which the works engage with the history and current political strife caused by sexism and racism. The Whitney Museum of American Art is highlighting protest throughout history and artists’ representations of of political revolt in an exhibition entitled An Incomplete History of Protest. Finally, The New Museum’s mounting of Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon, a show that explores gender fluidity as it relates to contemporary art, is a clear reaction to White House administration threatening womanhood in its many forms.

Throttling the spirit of conventional femininity led me to visit “Nkame,” the Belkis Ayón retrospective at El Museo del Barrio with some classmates from my ‘Re-Imagining Latin America’ class. Belkis Ayón is an Afro-Cubana printmaker working through a distinctly feminist lens. Earlier in 2017, her work was on exhibition at the Fowler Museum in Los Angeles and will be at El Museo del Barrio for the rest of the year. There was certainly a heaviness walking through the bountiful body of work she left behind. Her mysterious black and white artwork explores the mythology of ‘Abakua,’ an all male Afro-Cubano secret society. Belkis Ayón used strong female characters as a way of challenging gender norms. Figures have no facial expressions so you cannot readily decipher the gender. This was, of course, done on purpose. Like any good dreamer, Belkis Ayón envisions a society where racism and gender didn’t exist, where freedom and equality reigned. You could almost hear Ayon’s political dream lingering amongst her art.